Welcome to the April A to Z Blog Challenge! My theme this year is the Botany of the Realms of Imagination, in which I share a selection of the magical plants of folklore, fairy tale, and fantasy. You can find out about the A to Z Challenge here.

T seems to be a letter particularly richly grown with magical literary flora. I’ll start with one of my all-time favorites, the Truffula Tree. Truffula Trees have tall, slender trunks topped by bright-colored tufts. The touch of their tufts is much softer than silk, and they have the sweet smell of fresh butterfly milk. They’re also the favored habitat of Brown Bar-ba-loots, who eat the fruit of the Truffula Trees. However, because truffula silk is so excellent for knitting thneeds, the trees were severely over-harvested in the 20th century, and are now nearly extinct. Only careful conservation will be able to restore them and the beautiful habitat they provide - an appropriate reminder for Earth Day.

Another classic is the triffid, a tall species of carnivorous plant that can walk about on three stubby “legs.” Although they seem to have originated and spread faster in equatorial regions, triffids soon became invasive throughout the world. They can be quite dangerous because they have a venomous stinger in the head, but the stinger can be docked, rendering them harmless for the next two years while the stinger regrows, when they can be pruned again. When intact, the stinger is used to kill large prey instantly, which the triffid can then feed upon as it decomposes, plus they can also catch insects and small prey in the manner of a pitcher plant. Despite these dangerous characteristics, triffids can be economically very useful as a source of high-quality oil. Outside of oil farms, they are now mostly eradicated.

Tesla trees are native to the planet Hyperion, where they are the defining species of the Flame Forest. Named for the Tesla coil, these tall-trunked trees have a sort of bulb at the top in which they can store massive amounts of electricity that their branches draw in from static charge in the clouds. When the trees discharge this electricity in powerful jolts like lightning strikes, it causes wildfires, which drive the cycle of regeneration and growth in the forest.

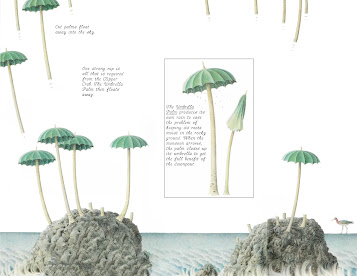

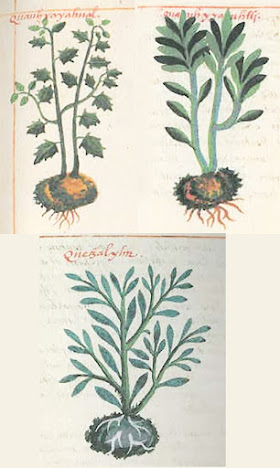

While we’re covering the classics, I have to mention the Tumtum tree, even though we don’t know much about it. In fact, all we know is that it grows in the tulgey wood, and is a good place to stand in uffish thought if you’re hoping to encounter a Jabberwock. Most artists don’t pay a lot of attention to the Tumtum tree, but here are details of the tree from three of the books that I featured back in my prior post A Jumble of Jabberwocks, plus one extra. Finally, a much less well-known plant, another of the parallel plants (first introduced at P) described by Lionni: the tiril. Of all parallel flora, tirils are the most widely distributed around the globe, and among the oldest. They live in dense groups, and although all parallel plants are black, tirils sport the widest array of black. (And by the way, parallel plants are generally matterless, indifferent to the passage of time, and impossible to photograph.) One tiril species has a habit of lodging itself ineradicably in the memory and occasionally forcibly reappearing in the mind. Another is a powerful aphrodisiac, and yet another species produces a loud, high-pitched whistle, but always stops as soon as anyone tries to get near enough to investigate.

Even now, the floral bounty of T is not quite exhausted, as you can always go back and revisit the triglav flower introduced at my post R is for Regeneration.

Gardening tip of the day for commercial triffid farmers: you can’t dock their stingers without lowering the quality of their oil, so be sure to wear protective gear and enforce strict safety protocols. Triffids know to aim for the exposed face and hands.

While the moral of triffids may be that many plants have immense commercial value, the moral of Truffula Trees is not to let exploitation of this commercial value get out of hand. The moral of Tumtum trees is that trees can be an excellent place to stand awhile, but the moral of Tesla trees is that sometimes it is not a good idea to stand under a tree: particularly during a thunderstorm. In short, you can surely find some plant to justify any moral at all that you’d like to draw!

What words of wisdom do you think people most need to hear? And what plant can be used to illustrate that moral?

[Pictures: Truffula Trees, illustration by Dr. Seuss from The Lorax, 1971;

Triffid, illustration by John Wyndham from The Day of the Triffids, 1951 (Image from Wikimedia Commons);

Tesla Trees, detail of cover illustration by Garry Ruddell from Hyperion by Dan Simmons, 1990 edition (Image from Fandom);

Tumtum Tree, detail of illustration by Joel Stewart from Jabberwocky, 2003;

Tumtum Tree, detail of illustration by Kevin Hawkes from Imagine That! Poems of Never-Was selected by Prelutsky, 1998;

Tumtum Tree, detail of illustration by Eric Copeland from Poetry for Young People: Lewis Carroll, ed. E. Mendelson, 2000;

Tumtum Tree, detail of illustration by Stéphane Jorisch from Jabberwocky, 2004;

Tirils, illustrations from Parallel Botany by Leo Lionni, 1977 (Images from Ariel S. Winter on Flickr).]